State-Level AI Governance

How do regulations at the state level affect federal regulation stories? What limits are there?

Intro

AI regulation is developing in the US, and options are being scaled and developed at a federal level. Individual states are getting involved as well; being smaller, holding discussions with fewer stakeholders, having a higher variance of viewpoints, and being legislatively nimbler than the federal government, there are also policy options here. What options do state-level governments have to regulate AI, and how can those regulations affect areas outside of their borders?

The following includes:

A few highlights of proposed or passed state-level regulations

Discussion of how state regulation in other domains has had larger effects outside of that state

An outline of limitations of powers that US states have in AI regulation in comparison to the federal government, especially as they relate to the Commerce Clause

Possible salient options for state-level regulation, including citizen protections and data center hardware

Current state-level AI policy bills

A sampling of state-level AI bills that have passed:

Colorado

The Colorado Privacy Act was enacted in May 2024. It adds further penalties when discrimination involves unchecked algorithmic bias in a 'significant decision' - examples of significant decisions include those for healthcare, housing, employment, or lending. Deployers need to do impact and risk assessments for their tools and need to report incidents of discrimination. Consumers have increased transparency on if AI systems are used to make significant decisions, and can appeal adverse decisions toward human review.

Utah

In Utah, SB149 was enacted in March 2024. Among other consumer protections, it requires generative artificial intelligence to disclose that it is an AI system and not a human if prompted and asked by a consumer. If the generative AI is used by a person in the course of a profession regulated by the state of Utah (e.g. the role requires a state certification) then the use of generative AI must be prominently displayed.

California

The Frontier Artificial Intelligence Models Act was proposed in February 2024 and is currently going through California’s legislative process. It applies to models “trained using a quantity of computing power greater than 10^26 integer or floating-point operations, the cost of which exceeds one hundred million dollars ($100,000,000)”, models of which do not yet exist, to submit information regarding the capacity of the model to cause harm. It also requires computing clusters to verify the identity and purpose of those who intend to train such models.

Effects of state regulation outside of their borders

The effects of that state-level legislation can have wider effects on US policy either in other states or at the federal level, and stories of the development of current regulatory regimes bear this out. State regulations can:

Serve as a proof of concept for proposals elsewhere

Affect how companies design their products for sale in other localities

Allow those states to be bolder when advocating for similar agreements at a federal level

State regulations serve as a proof-of-concept

In 2006, New York City banned the sale of foods containing trans fats in its restaurants.1 Trans fats are often used in margarine or shortening, as well as some fried or baked goods, and are known to cause negative effects on cardiovascular health. In response, restaurants adapted their practices, and ingredient suppliers adapted their offerings. Nothing much seemed to go awry, and since it remained politically viable, similar bans sprung up elsewhere. Philadelphia banned trans fats in 2007, then California2 and Boston3 in 2008. In 2018 the FDA largely removed partially hydrogenated oils from the US food supply4 and the NYC ban is now lauded as a public health success.5

Other similar proof-of-concept stories can be observed in the passing of minimum wage laws (Massachusetts), physician-assisted suicide (Oregon), marijuana legalization (Colorado and Washington), and no-fault divorce (California).

Individual states may not be willing to be a first mover on particular AI policies - doing so would mean they need to develop a legal framework themselves, and there is higher uncertainty about the feasibility of the policy or the political consequences. If individual bolder states can provide a proof-of-concept then other states, or the federal government, may find it easier to follow suit.

State regulations affect how companies design their products for sale in other localities

California started regulating automobile emissions in 1967, shortly before the federal Air Quality Act that same year and a few years before the federal Clean Air Act of 1970. Since that time, California has held a series of waivers that allow its regulations to be stricter than those of the federal government, partly due to the poor state air quality in its major cities.

In 1970, California used that allowance for creating strict emission standards to address the design of cars that were sold within its state borders. GDP in California at that time comprised ~10% of the US economy - manufacturers therefore had strong incentives to develop cars that would meet California's standards. Since the state pushed companies to develop designs and technology that met its standards, the federal government was able to pile on and more easily pass a nationwide requirement for catalytic converters later in 1975.

The economic power of the state matters in this case. The three states with the highest GDP are California, Texas, and New York. If these were ranked alongside countries in terms of their GDP, California would come in at #5, Texas at #9, and New York at #11. These are large markets, and companies want to have suitable products.

When product-related regulations are passed it's often easier for a company to change the design for one product rather than go through the process of selling two separate products from two different or split production lines. For AI, if certain states create regulations addressing the practices of developers or deployers this can affect what shows up as the default product for other states or countries.

Other examples of this type include GDPR (The EU), product chemical warnings (California), and history textbook content (Texas).

States with regulation can be bolder when advocating for similar agreements at a federal level

Women were given the right to vote in the US in 1920 via an amendment to the US Constitution. By the time the amendment was voted on at a federal level, fifteen states had already passed similar laws in their states. At a minimum, representatives for those states had little reason to oppose the amendment as the matter was already clearly resolved in their own state.

Similarly, before the Montreal Protocol in 1987, which created a phase-out ban on ozone-depleting chlorofluorocarbons, several countries already had bans of their own.6 By 1980 aerosol uses for CFCs were heavily regulated in the US, Norway, Canada, and Sweden.7 Since these countries had already made strong commitments domestically, they were able to hold a stronger position against other groups when coming together for international discussions.

The case with AI regulation is somewhat different - states are currently going different directions when addressing concerns about AI, which means there isn't clear momentum toward something specific as a group or at a federal level. Nevertheless, as states create their own regulations and task forces they position their representatives at a federal level to address issues of AI governance in kind. When there are broader federal proposals for AI regulation, if more states already have laws in place regulating AI there may be greater interest and agreement in the proposals.

Limitations to state-level AI policy

Although state-level policies may have outsized effects, they do have fewer options than the federal government, which can pass legislation toward military or foreign relations objectives, and has control over immigration policy and foreign relations.

Additionally, since commerce related to AI is occurring over state lines, it does impinge upon federal responsibilities and interests; understanding the AI policy options available to states cannot be grappled with without first understanding how the federal government is involved in interstate commerce. Allow me to introduce (or re-introduce) you to...

The US Constitution's Commerce Clause

An individual state's ability to regulate commerce-related issues is sharply framed by the Commerce Clause in the US Constitution:

[The Congress shall have Power] To regulate Commerce with foreign Nations, and among the several States, and with the Indian Tribes

While initially used to prevent states from discriminating against each other,8 the Commerce Clause eventually developed to ensure federal supremacy in commerce-related issues between states. Illustrative examples include:

Crosby v. National Foreign Trade Council (2000), which invalidated a Massachusetts law banning the import of goods or services from Myanmar on the grounds that the state law was pre-empted by federal legislation – a state law banning foreign imports would interfere with the federal government’s authority to regulate foreign trade.

Gibbons v. Ogden (1824) invalidated a New York law which gave a steamboat operator exclusive right to shipping within New York state, conflicting with a license another operator had from the federal government for the same waterways. This clarified that the federal government not only had primacy over interstate commerce but also intrastate commerce.

For this reason, AI chip regulation in states that hold major international ports would be untenable. If a state imposed import controls which require certain hardware features, or established outright import bans of chips from certain sources, such regulations would be struck down by the Commerce Clause.

Also, since American Libraries Association v. Pataki (1997), the internet has been recognized as part of interstate commerce - extraterritorial applications of state law to transactions involving citizens of other states violates the Commerce Clause especially since applications of law would be more uniform and more consistent at a federal level. For this reason, states couldn't, say, ban the transfer of AI-generated images over the internet.

So, where does this leave commerce-related opportunities to regulate AI at a state level?

For a state to be permitted to regulate something that affects interstate commerce it must satisfy the following conditions:9

legitimate local public interest, and

any negative effects on interstate commerce must be

incidental,

not clearly outweigh (1), and

there must not be other less discriminatory options available.

Some illustrative examples:

Maine v. Taylor (1986) affirmed the right of the state of Maine to ban the import of live baitfish to protect its own fisheries from parasites and non-native species from out-of-state baitfish imports. This was upheld as serving a legitimate local interest.

Dean Milk Co. v. City of Madison (1951) held that a Wisconsin law, requiring milk to be pasteurized at an approved plant within 5 miles of the city, unconstitutionally discriminated against interstate commerce. "...Madison plainly discriminates against interstate commerce. This it cannot do, even in the exercise of its unquestioned power to protect the health and safety of the people, if reasonable nondiscriminatory alternatives... are available"

If AI regulations (that affect interstate commerce) are to succeed at a state level, they need to clearly give a benefit to the citizens of that state.

So what options are available for state-level regulation?

Salient options for state-level AI policy

Good policy options here would not conflict with the supremacy of the federal government and would also take advantage of a state’s individual interests and resources. If done well, it will not only provide value for citizens within that state but will also have continuing effects on the development of state and federal policy.

The following contains a few categories of options for policies and is by no means exhaustive. The two categories that are explored are protecting the interests of citizens and data center hardware regulation.

Protecting the interests of citizens

States have significant authority to affect the behavior of government systems and businesses in their own state. To protect the rights and interests of their citizens, states can change how AI tools are implemented. This is broadly where current state-level AI regulation resides, and further proposals and testing in this area will be helpful overall.

Example policy categories include:

Profiling. Many new state-level AI laws are putting restrictions on consumer profiling, but there are many other ways AI-assisted profiling could be used, including in the courts, parole boards, law enforcement and healthcare, or for employment, insurance, lending, or university applications.

Surveillance. The use of AI could be used to observe and aggregate information and assessments of employees, prisoners, detainees, or students.

Disclosure. Informing consumers when they are interacting with an AI rather than a human can give them context and power to appeal automated decisions.

Data centers and hardware regulation

States govern a geographic area, but the development of AI often does not have a clear physical regulatable presence. One exception is data centers, which are important because:

Data centers are where AI chips live

There are various hardware-based avenues in AI safety.10 11 These include:

Only hosting AI chips from certain manufacturers that have tracked serial numbers or other security features

Verifying the identity and purpose of customers using AI chips

Remote shutdown buttons

Regulation on hardware is often discussed in the context of regulating AI developers and deployers more directly, which means either regulating developers or deployers in the states where they reside or at the federal level - but if AI companies need data centers, this could be a useful, though a somewhat more distant, approach.

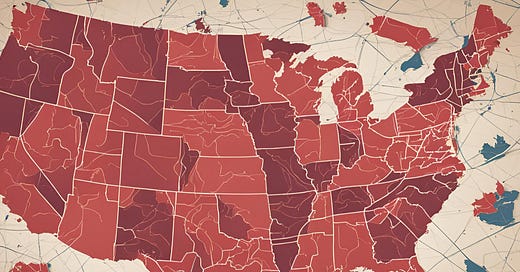

Also, as it turns out, data centers are moderately concentrated in a few states. In 2023, over 50% of all power load for US data centers occurred in only five states (Virginia, Texas, California, Illinois, and Oregon). Virginia alone accounted for 22% of power load in US data centers.12

A workaround for AI companies could of course be to use or build data centers in other states without those regulations. This strategy would at the very least cause a delay. Existing data centers are currently being put to use, which is why new ones are being rapidly built.13 New data centers take 1-2 years to construct and would be in less ideal locations.14 15 16

Does state-level data center regulation run up against the US Commerce Clause? Uncertain.

There are unimpeded state laws that affect the practices of internet services hardware:

23 NYCRR 500 is a 2018 New York law that puts cybersecurity requirements on its financial services firms.

SB 327 is a 2019 California law that requires router and IoT device manufacturers to equip reasonable security features for devices sold in California.

Such laws undoubtedly increase the cost for the affected businesses and increase prices for their in-state and out-of-state consumers, but the security benefits to in-state consumers seem to be sufficient to maintain justification for these laws. Such laws have a more direct benefit to citizens, whose data is being stored by financial services firms or IoT manufacturers. On the other hand, regulating hardware for AI chips in data centers that happen to be in that state is a few more conceptual jumps away from protecting a citizen’s security for that state in particular.

There also is a question of political will, which will be different from state to state. Virginia, for example, offers tax incentives to data centers on the basis that they will create jobs and other tax revenue, and also has policies and a task force that are addressing the use of AI, which indicates some awareness of potential harms. If hardware regulation on a state level is possible, it will require various stakeholders.

It’s also plausible that the locations for AI compute clusters do not have the same location requirements when compared to the uses of data centers in the past, meaning that regulation of states that currently have large proportions of data centers could miss the mark. Data center locations are partly chosen based upon close proximity to undersea cables and good network infrastructure, as their customers nationally and internationally need fast access to data or cloud computing services. For AI training runs, however, connectivity to the rest of the world may be less important. Nonetheless, current locations of data centers offer expertise and viable space, meaning that data centers used for AI training may be in the same locations as data centers used for other uses such as data storage and cloud computing.

The concentration of data centers at a state level may or may not present a feasible strategy for regulation. It would be well worthwhile for policymakers in states with significant portions of data centers to see what policies are possible in their state.

End

The US federal government naturally has substantially more power than states to create effective AI policies. Development and implementation of AI policy is still in early days however, and the past has shown that smaller nimbler states can pass regulatory policies which, aside from protecting those within their borders, can also influence those outside of them.

https://www.nyc.gov/assets/doh/downloads/pdf/cardio/cardio-transfat-bro.pdf

https://emd.saccounty.gov/EH/FoodProtect-RetailFood/Documents/CCDEHTransFatBanGuidelines.pdf

https://www.boston.gov/sites/default/files/file/2021/03/Trans%20Fat%20Guidelines%C2%A0.pdf

https://www.fda.gov/food/food-additives-petitions/final-determination-regarding-partially-hydrogenated-oils-removing-trans-fat

https://www.statnews.com/2017/04/12/trans-fat-new-york-heart-attack/

https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/countries-to-montreal-protocol-and-vienna-convention

https://www.epa.gov/archive/epa/aboutepa/statement-international-meeting-chlorofluorocarbons.html#:~:text=Sweden%20and%20Norway%20have%20banned,to%20consider%20taking%20similar%20steps.

https://scholar.google.com/scholar_case?case=15647611274064109718#:~:text=For%20the%20first%20century%20of%20our%20history%2C%20the%20primary%20use%20of%20the%20Clause%20was%20to%20preclude%20the%20kind%20of%20discriminatory%20state%20legislation%20that%20had%20once%20been%20permissible

https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/397/137/#:~:text=Although%20the%20criteria,on%20interstate%20activities.

https://www.cser.ac.uk/media/uploads/files/Computing-Power-and-the-Governance-of-AI.pdf

https://www.openphilanthropy.org/research/12-tentative-ideas-for-us-ai-policy/#:~:text=Require%20hardware%20security%20features%20on%20cutting%2Dedge%20chips.

https://www.epri.com/research/products/3002028905

https://www.cbre.com/insights/reports/north-america-data-center-trends-h2-2023#:~:text=Figure%205%3A%20Primary%20Markets%20Historic%20Net%20Absorption%2C%20Preleasing%20%26%20Under%20Construction

https://www.datacenterdynamics.com/en/analysis/the-data-center-life-story/#:~:text=it%20built%20quickly.-,The%20building%20time,-is%20normally%20measured

https://www.stackinfra.com/resources/blog/how-speed-to-market-is-transforming-data-center-design-and-construction/#:~:text=data%20center%20design%20and%20construction%20processes

https://dgtlinfra.com/building-data-center-construction/#:~:text=(typically%2018%20to%2024%20months)